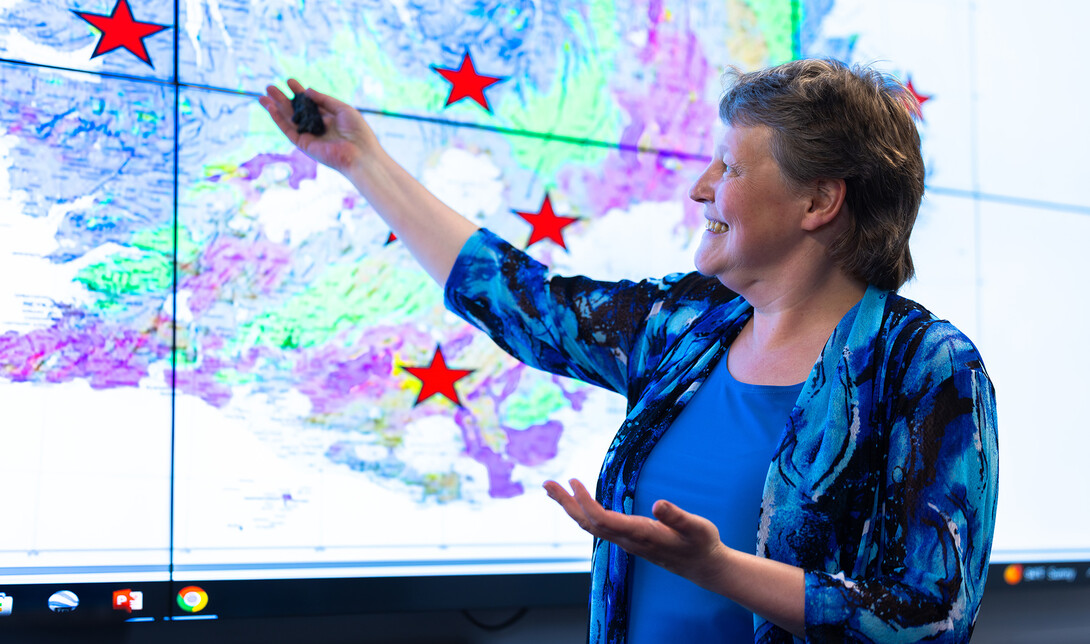

Husker geophysicist Irina Filina has been selected as a Fulbright U.S. Scholar and will travel to Iceland in summer 2026 to collect data for her ongoing research into the proposed continent of Icelandia.

Filina, associate professor of Earth and atmospheric sciences, also proposed to offer an educational abroad experience for undergraduate and graduate students.

The discovery of continental material around Iceland started an international debate among scientists in the last decade: Could Iceland really be just the tip of a larger continent? Since, Filina has been actively engaged in research helping to answer that question. Her Fulbright proposal includes collecting field observations by visiting at least three sites to further computer modeling of the Earth’s crusts in the North Atlantic Ocean.

“It was believed that the crust (around Iceland) was oceanic for decades, centuries, but in 2020 a paper proposed that the crust is not actually oceanic, but continental,” Filina said. “It broke the scientific community into the different camps, and people are debating about it. We know there is a portion of continental crust, but there is debate about how big it is and what the boundaries are.”

The research — and scientific debate — challenges long-held ideas about the complex tectonic region that is the North Atlantic and could change how scientists understand the formation of new continents and oceans.

“We are witnessing global changes right now. In geology, we usually talk about much larger time frames — millions of years — but we are seeing changes, and we see that they can happen really, really fast."

Filina will partner with the Iceland Geological Survey team and colleagues from the University of Iceland to study felsic lavas and other geological formations across Iceland. The data collected will be used in the ongoing geophysical modeling Filina and her team are conducting to help answer the Icelandia question.

“We cannot just drill through the crust and determine its nature — it's too deep for us to reach,” Filina said. “However, we can combine and integrate different types of data and find a solution that acknowledges all the observations that we have.”

The opportunity to spend three months in Iceland collecting new data builds on the ongoing research Filina is conducting under her 2023-2028 National Science Foundation Early Career Development Program award, which focuses on the tectonics of the North Atlantic, and her selection as a scientist on the International Ocean Discovery Program 396 in 2021.

“That expedition triggered my curiosity about the tectonic story of the region,” she said.

Filina is planning a three-week course in Iceland for Husker undergraduate and graduate students, where they will do coursework in geology and take field trips to learn more about Iceland’s geological formations, geothermal plants and efforts in carbon sequestration.

“I think it will provide students with a fantastic opportunity to go abroad to see interesting geological phenomena that may initiate some research directions and, maybe, some careers,” Filina said.

The Fulbright award is meaningful to Filina personally and as a scientist, and the research could impact how the formation of the Earth is understood, which is especially important now.

“We are witnessing global changes right now,” Filina said. “In geology, we usually talk about much larger time frames — millions of years — but we are seeing changes, and we see that they can happen really, really fast.

“In order to explain or predict future changes, we have to understand how our planet works, and for that, we must understand the past. The past is the key to the future. We want to be able to reconstruct that area and understand the tectonic evolution to the best of our ability in order to predict what will happen.”