Through a $769,792 grant from the National Science Foundation, Husker scientist Richard Wilson is continuing work to unravel the mysteries behind effectors — virulent proteins that short-circuit plants’ natural defenses against fungal disease.

The project expands on Wilson’s previous NSF-funded work that began pulling back the curtain on fungal-secreted effectors that use multiple tactics to help pathogens attack and destroy crops.

Wilson’s focus is Magnaporthe oryzae, the rice blast fungus that annually destroys up to 30% of global rice production. Rice blast “is the most serious disease of cultivated rice, with enough rice destroyed by the fungus each year to feed 50 million people,” said Wilson, Charles Bessey Professor of plant pathology at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln.

Although the project focuses on boosting rice resistance to infection, the scientific findings can also be applied to a range of other grain crops and grasses vulnerable to pathogenic assault.

In paving the way for fungal infection, effectors mutate opportunistically and attack the rice plant in varying ways — suppressing its immune response, modifying its physiology or reprogramming its internal environment. If this were a science fiction story, effectors could be broadly likened to nimble, shape-shifting outer space warriors that unpredictably modify their bodies and attack the hero with an alternating set of superpowers.

Effectors are particularly challenging because, unlike conventional proteins, as a group they lack a common genetic sequence and stand out for how readily their genes mutate, rearrange or disappear entirely. This quixotic character makes effectors hard for scientists to identify through conventional bioinformatics analysis.

“They have no features to tell us what they might do, or where they might go, or whether they’re going to go into the plant,” Wilson said. “Effectors are extremely important to find, but difficult to find.”

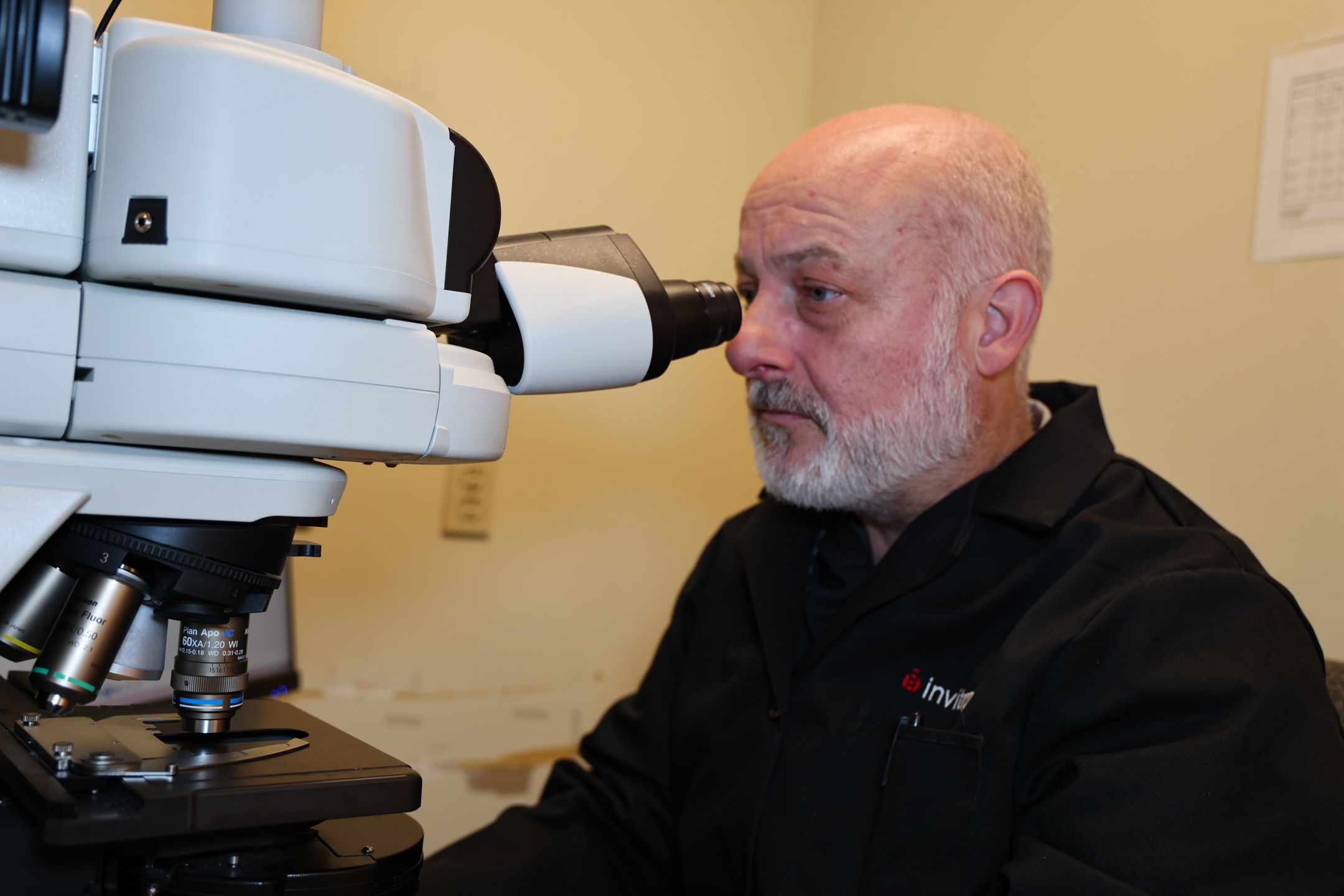

Wilson is internationally recognized for his contributions to understanding plant-microbe interactions, and in 2023 the American Association for the Advancement of Science named him one of its fellows for his important contributions to the field.

If scientists can make progress in identifying effectors’ key biological basics, the discoveries can open the way to major advances in plant resistance. The NSF’s continued support for Wilson underscores the university’s prominence in this area of science.

To peel back this scientific mystery, Wilson and his team — doctoral students Nawaraj Dulal and Nisha Rokaya and master’s student Ben Wheeler — are using innovative methods in genetic analysis to pursue key goals:

- Better predict which fungal proteins are effectors;

- Understand how pathogens fine-tune effector release to maintain infection;

- Pinpoint the signal that allows secretion of effectors into plant cells.

The team uses Magnaporthe oryzae for its research because the fungus’ extensive genetic information provides a model system for understanding plant-fungal interactions and for the applicability of the research findings to other major cereal crops.

The title for Wilson’s NSF grant application (“Cracking the codon code for pathogen effector secretion in host plant cells”) refers to how the Husker team is analyzing a less-understood but crucial cellular pathway that channels the development of hostile effectors. The more that Wilson and his colleagues can unravel the details of that process, the stronger the scientific understanding of the overall rules governing effector creation and mutation.

Computational modeling estimates that Magnaporthe oryzae likely has about 1,800 “candidate genes” with potential to produce host plant infection-specific effectors, but only a handful have been identified. The Husker team’s innovative analytical methods are expected to greatly advance the ability to identify the genes.

“We think we can accelerate that tenfold going forward,” Wilson said. “It should be a very fast way to identify new effectors and get the pipeline moving.”

That expanded knowledge hopefully can lead to identification of resistance genes in host plants, which opens the way to a range of long-term agricultural benefits. Plant breeders would be better able to develop cultivars with stronger defenses against attack. More effective fungicides could become possible.

Long term, genetic engineering could place identified resistance genes in new cultivars, greatly boosting their protective capability.

Such benefits needn’t be limited to cultivated rice, since Magnaporthe oryzae infects dozens of plant species, including wheat, rye and barley, as well as a range of turfgrasses. Although there are no reports of infection in U.S. wheat at present, experiences in the global seed trade demonstrate any country’s potential vulnerability to spread of the fungus.

The Husker project offers important research and experiential learning opportunities for undergraduate and graduate students, Wilson said, and the researchers are aided greatly by the world-class quality of its laboratories, greenhouses and equipment.

“We have everything we need here,” he said. “There’s no doubt about it.”